How I Learned to Love Practicing, Again

A serious bicycle accident required some equally serious rehab of my left hand.

I recently posted to Instagram a couple of video clips of fingerboard exercises I’d been working on. These kinds of extended exercises are not the sort of thing I’ve spent much time on for probably forty years; not since my late ‘20s. During the last four decades, most of the music I’ve played hasn’t been too technically demanding. By my early thirties, I had a pretty good command of the fingerboard, at least for the music I was playing. Jazz in the 1980s wasn’t as theoretical as it seems to be now. Being comfortable with the modes of the major scale, as well as a handful of other scales (diminished, altered, melodic minor, etc.) and their corresponding chords, in all positions and in most keys, was enough. And bluegrass in the ‘90s wasn’t the shred-fest it is today, or at least I didn’t feel I had to prove my worth through note counts and blistering speed. So, practice for me had mostly consisted of learning new tunes, memorizing tunes for gigs and sessions (or my Peghead Nation lessons), composing, and exploring other kinds of music. Of course, there was the occasional tune that needed a lot of practice, but nothing really required that I work on technique to any extent, for either hand.

But that all changed two years ago when I had a serious bike accident. I broke my collarbone and fractured two ribs, which laid me up for a few weeks, but the long-lasting injury came from a laceration to my left index finger that kept me from using that finger for two months. And, unfortunately, I didn’t start using it to play the guitar for at least a month more. The damage was not from a cut, but from my index finger literally exploding when I landed on it after suffering a syncope (losing consciousness) while riding. Since I was unconscious, I didn’t brace myself as I fell, so my left hand and arm took the full weight of my body when I hit the pavement.

The laceration and a gnarly scab took a long time to heal, and I refrained from moving the finger very much until the swelling went down. This was a mistake, as I learned from the first hand specialist I saw four months after the crash, who explained that the reason I could barely bend the second joint of my index finger was not because of the swelling but because I hadn’t moved it in months. (The finger apparently decides that if you’re not going to use it, why should it bother paying attention when the brain sends it signals to get moving.) So, rehabbing my hand (my middle and ring finger were also bruised and sore) was going to take some serious work.

I started by revisiting some of the slur exercises I used as warmups before gigs. These exercises can be found in Scott Tennant’s book Pumping Nylon, an essential resource for budding classical guitarists, but I originally learned them from classical guitarist Tom Patterson when we were both teaching at the 1981 Puget Sound Guitar Workshop. They’re great exercises for warming up all the fretting-hand fingers equally, but I would usually spend at most ten or fifteen minutes a day on them, at home or backstage before a gig. In August of 2021, however, I didn’t need to just warm up my hand; I needed to rehab it.

I spent three months in Chile that fall and I had a lot of extra time to practice. I started by trying to play all of the single-note melodies I could think of: my own tunes, old-time fiddle tunes, bebop lines, etc. I started slowly and quickly discovered what my fingers could do and what they couldn’t. After a while, I realized that my fingers’ muscle memories also seemed to be damaged. I would start a tune I thought I could play in my sleep but then suddenly I would find my fingers on some random, unexpected frets, which, unfortunately, didn’t turn out to be some cool, spontaneous variations.

The other problem was that playing in “cowboy chord” position was painful and at first not doable at all. I couldn’t play a cowboy C chord without damping the high E string, and I had similar problems with open E and A chords. (While playing an open A chord during a session backing up fiddler Chad Manning for a Peghead Nation video lesson my index finger kept folding over and fretting the F natural on the E string—not a pleasant sound.)

I found that my hand was more comfortable playing in “classical” position, with my fingers stretched out so they’re almost parallel with the frets. I could even play chords with four- and five-fret reaches, with my index finger barring the top two strings. It became clear that I would have to come up with exercises that addressed the specific weaknesses of my fingers. I re-examined the exercises in Pumping Nylon, found a few others I’d ignored that helped quite a bit, and started developing and varying others.

Since my hand didn’t have as much trouble with “jazz” chords as with cowboy chords, I spent a lot of time on chord-melody arrangements of some favorite jazz standards, a few of which I had worked up in the 1980s or ‘90s, and some I worked up for the first time that fall. I also got more into scale exercises, working on the different fingerboard positions of the modes of the melodic minor scale, for example, and coming up with new patterns and sequences. I found myself diving into music books and instructional videos, looking for licks and lines I could turn into exercises.

I ended up spending as much two to three hours a day on technique that fall, which may not sound like much for some people, but for me, at the age of 67, working at my Peghead Nation job remotely, and living with my in-laws, who didn’t speak English, it was a lot of work. And I loved it!

Getting my hand in shape allowed me to compose and record the album Flown South after I returned to the US. And I rediscovered my love for the guitar again, after a few years of not playing regularly. Although I don’t have much time to practice these days (I’m currently trying to spend an hour or two a day studying Spanish) I do practice most days, and I usually start out with 20 minutes or more of exercises.

Here are a couple things I’ve been working on.

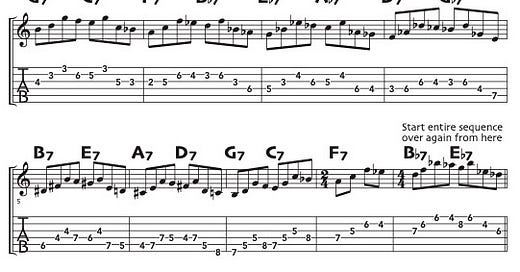

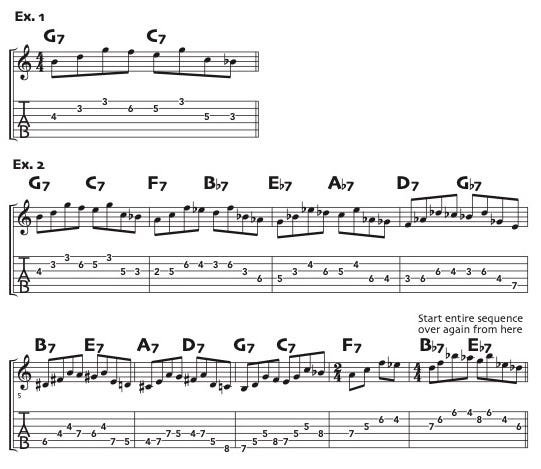

The first circle-of-fifths exercise video I posted originated with Yusef Lateef’s book Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns, the first couple of pages of which have some four-note phrases moving around the circle of fifths. I combined two four-note patterns into a one-measure, two-chord pattern (starting with G7–C7, Example I in the music below) and then started exploring different fingerings.

I finally found a fingering pattern that moved across the fingerboard, rather than up or down, and completed the circle on the low E string two frets above where I started. I then used the first four-note phrase to move back across the fingerboard, where I started over again on a Bb7 chord (this whole sequence is in Example 2). The sequence moves up the fingerboard by a minor third and completes four sequences and finishes on a G an octave above where I started. (In the video, I started on an F#7 so I could finger the last few chords more easily.)

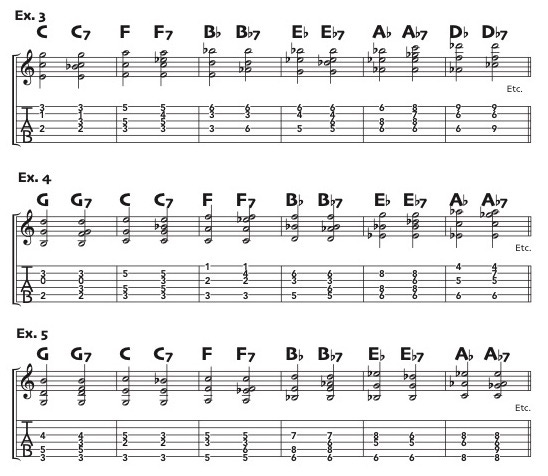

The second circle-of-fifths video came from an idea in one of Kurt Rosenwinkel’s Master Class videos. It basically involves moving triad and seventh voicings spanning four strings (“drop-D vioicings” in guitar lingo) around the circle of fifths, moving up the neck each time to the next closest inversion. In this case I start with a first-inversion voicing of C–C7 on the top four strings, followed by root position for F–F7 and second inversion for Bb–Bb7 (Example 3). Then I repeat the pattern on the middle four strings starting with G–G7 (Example 4) and again on the bottom four strings with G–G7 again (Example 5).

I’ll probably keep posting some of the more interesting exercises I’m working on to Instagram. It makes me focus on them if I have to get them ready to “perform.” If you’re a subscriber to Chops Talks, let me know if you want music for any of them after I’ve posted them. As with the music here, I’ll give you the basic idea, and let you work out the entire thing yourself. You don’t really learn anything if you don’t have to work at it a bit.